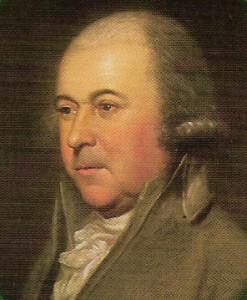

The most indispensable person at the Second Continental Congress leading up to July 4, 1776 was not Thomas Jefferson (who, though authoring the Declaration, said hardly a word at the Congress). It was the significantly less well-liked and often pugnacious, but ever intellectually sharp debater, John Adams. Adams served on nearly every committee of significance in the Second Continental Congress. He was consistently the most fervent proponent of independence from Great Britain and, in terms of reasoned argument, the most effective.

It was Adams who passed to Jefferson the responsibility of writing the Declaration. As Adams recounted later in a letter to Thomas Pickering, he explained to Jefferson why Jefferson and not he, Adams, should be the principal author: “Reason first – you are a Virginian, and a Virginian ought to appear at the head of this business. Reason second – I am obnoxious, suspected, and unpopular. You are very much otherwise. Reason third – you can write ten times better than I can.”

It was Adams who rose from his seat on July 1, the day on which the resolution of Independence (not the wording of Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration) was debated, to be the first to respond to the speech of John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, leader of the “Olive Branch” faction. As historian David McCullough notes, “No transcription was made, no notes were kept. There would be only Adams’s own recollections, plus those of several others who would remember more the force of Adams himself than any particular thing he said. That it was the most powerful and important speech heard in the Congress since it first convened, and the greatest speech of Adams’s life, there is no question.”

It is reasonable to suppose, as McCullough does, that some of Adams’s July 1 speech may have been along the lines of these words that he had recently written to a friend:

Objects of the most stupendous magnitude, measures in which the lives and liberties of millions, born and unborn are most essentially interested, are now before us. We are in the very midst of a revolution, the most complete, unexpected, and remarkable of any in the history of the world.

Again, McCullough:

“To Jefferson, Adams was ‘not graceful nor elegant, nor remarkably fluent,’ but spoke ‘with a power of thought and expression that moved us from our seats.’ Recalling the moment long afterward, Adams would say he had been carried out of himself, ‘”carried out in spirit,” as enthusiastic preachers sometimes express themselves.” To Richard Stockton, one of the new delegates from New Jersey, Adams was ‘the Atlas’ of the hour, ‘the man to whom the country is most indebted for the great measure of independency…. He it was who sustained the debate, and by the force of reasoning demonstrated not only the justice, but the expediency of the measure.’

“Stockton and two other new delegates from New Jersey, Francis Hopkinson and the Reverend John Witherspoon, famous Presbyterian preacher and president of the College of New Jersey at Princeton, had come into the chamber an hour or so after Adams had taken the floor and was nearly finished speaking. [The three New Jersey delegates were arriving to take their place as new members of Congress, and had been caught in the violent thunderstorm — their clothes were soaking wet. The storm had delayed them.] When they asked that Adams repeat what they had missed, he objected. He was not an actor there to entertain an audience, he said good-naturedly. But at the urging of Edward Rutledge [delegate from South Carolina], who told Adams that only he had the facts at this command, Adams relinquished and gave the speech a second time ‘in as concise a manner as I could, ’til at length the New Jersey gentlemen said they were fully satisfied and ready for the question.’ By then he had been on his feet for two hours.

“Others spoke, including Witherspoon, the first clergyman to serve in Congress, whose manner of speech made plain his Scottish origins. In all, the debate lasted nine hours. At one point, according to Adams, Hewes of North Carolina, who had long opposed separation from Britain, ‘started suddenly upright, and lifting up both his hands to Heaven, as if he had been in a trance, cried out, “It is done! and I will abide by it.”’”

When the vote was taken, nine out of the thirteen colonies voted for independence. Pennsylvania’s delegation voted four to three against it (with Benjamin Franklin in the minority). South Carolina’s delegates too voted “no.” New York abstained. Delaware’s two present delegates were divided; the third, Caesar Rodney, one of the strongest delegates for independence was nowhere to be found. Edward Rutledge had the bright idea to postpone a final vote till July 2, in the hope that the remaining hold-out delegations (especially his own) might be swayed.

On the next day, July 2, John Dickinson and another anti-Independence Pennsylvania delegate absented themselves so as not to stand in the way of independence. A mud-spattered Caesar Rodney arrived just as the doors to Congress were about to be closed at 9 AM, having “ridden eighty miles though the night, changing horses several times, to be there in time to cast the vote” (DM). Delaware would now vote “yes.” South Carolina’s delegates joined the “yes” vote. New York’s delegates abstained, making it possible to assert that no colony voted against independence.

Adams wrote to his wife Abigail (here we can forgive him for being wrong about the precise date, given his prescience about the historic character of the event):

The second day of July 1776 will be the most memorable epocha in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the Day of Deliverance by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells bonfires, and illumination from one end of this country to the other from this time forward forever more. You will think me transported with enthusiasm, but I am not. I am well aware of the toil and blood and treasure that it will cost us to maintain this Declaration and support and defend these states, yet through all the gloom I can see the ravishing light and glory. I can see the end is worth more than all the means, and that posterity will triumph in this day’s transactions, even although we shall rue it, which I trust to God we shall not.

As McCullough notes: “That the hand of God was involved in the birth of the new nation [Adams] had no doubt. ‘It is the will of heaven that the two countries should be sundered forever.’ If the people now were to have ‘unbounded power’ … and thus high risks were involved, he would submit all his hopes and fears to an overruling providence, ‘in which unfashionable as the faith may be, I firmly believe.’”

On July 3 Congress met to produce a final version of the Declaration of Independence from Jefferson’s draft. About a quarter of Jefferson’s draft was excised, including the climactic criticism of King George for perpetuating the horror of the slave trade (a criticism that Adams strongly endorsed). During the debate about Jefferson’s draft, as McCullough notes,

“Adams did not sit silently by. He was present every hour, ‘fighting fearlessly for every word,’ as Jefferson would write. ‘No man better merited than Mr. John Adams…. He was the pillar of its support [viz., of the wording of Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration], its ablest advocate and defender against the multifarious assaults encountered.’ Finally, to Jefferson’s concluding line was added the phrase ‘with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence,’ an addition that Adams assuredly welcomed.”

Debate on Jefferson’s draft continued until 11 AM on July 4, when twelve colonies approved the final version and New York abstained. Congress ordered that the document be printed. Only President John Hancock and Secretary Charles Thomson put their signatures on the document. It would not be until August 2 when Adams and fifty other delegates still present would sign the official copy. It was not until July 5 that the first printings were produced, not until July 6 that the first newspaper published the full text for a wider audience, not until July 8 that the first public celebration occurred (in Philadelphia), and not until July 10 that George Washington had the document read to his troops in New York.

Here is a clip from the HBO miniseries John Adams (2008) depicting the July 1 speech for independence by John Adams (played by Paul Giamatti). Since we don’t know exactly what Adams said, the film’s screenwriter collaborated with historian David McCullough to produce a mini-summary of what Adams might have said in his two-hour speech.

The line about “a republic of laws, and not of men” is particularly stirring (it was a phrase actually used by Adams in his “Novanglus Essays” 1774–1775). These words are all the more poignant in view of the recent tyranny of Five Lawless Justices of the United States Supreme Court, unelected jurists who have legislated coercively against the American people on “gay marriage” what the American people have not legislated for themselves, through some fairy dust sprinkled onto the Fourteenth Amendment. May God restore to this country representative democracy in place of judicial tyranny, a government deriving "just powers from the consent of the governed."

[Thanks to Rev. Kevin DeYoung for directing my attention to the HBO clip and the phrase “a republic of laws…” through his own post here.]